內容簡介

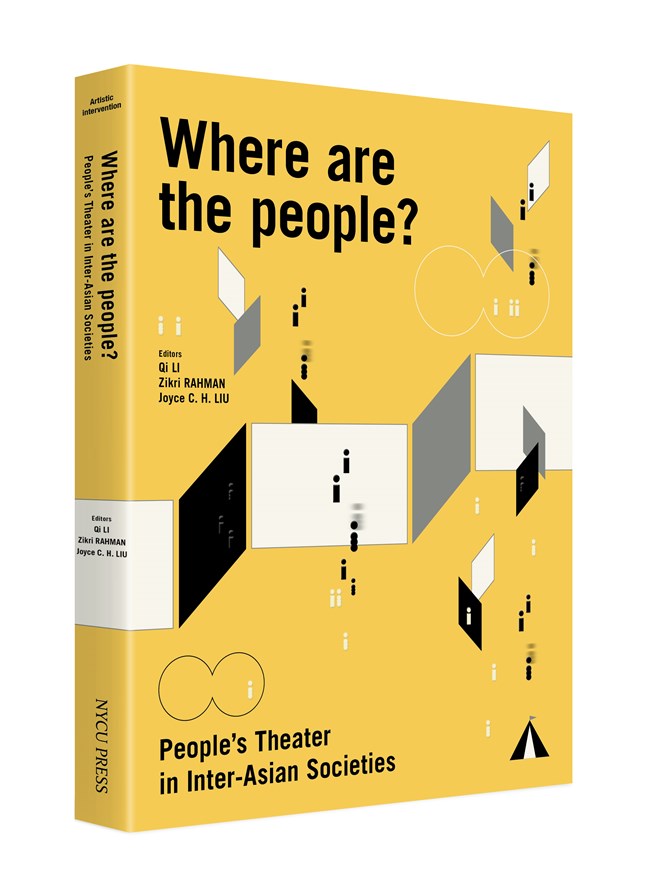

內容簡介 Where Are the People? How Could the People’s Bodies Voice Themselves in the Form of Theatrical Aesthetics? At That Time, the Audience Really Stood Up. In this evening, theater practitioners initiated the conversation with physical action. They engage with contemporary issues through their unique performance styles. From a discursive context, they enter the scene of resistance and undertake the labor of performance. Their performance is not just the preface to a series of dialogues, but also a witness to thirty years of People’s Theater. “People’s theater” belongs to the people. It is the theater created by the people and speaks for the people as it has appeared in history in diverse forms. People theater in Inter-Asian Societies began to grow in a cross-region, which included Jakarta, Manila, Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur, Hong Kong, Tokyo, Busan, Maputo, Beijing, Shanghai, Hualien, Taichung, and Taipei. Through the writings and images written down by theatrical artists from these spaces, we can figure out the body aesthetics that carry historical conflicts and the experience to find the form and channel of expression, and continue for work of thinking and creation. “People Theater” is nothing but a rehearsal for a revolution. This book has reviewed and reflected on the half-century development of people’s theater in inter-Asian societies, demonstrates how the theatrical practitioners and artists in different communities strived to open various spaces, dealt with the censorship from the authoritarian regime to the neoliberal societies, and experimented with diverse aesthetics and local objects to address political issues. ▍Preface “It is a collection with the premise that can motivate our critical thinking with bodily energy. It reflects how we realize the statement—‘Viewing as participating; audience as actors.’It is also a book where some keywords constantly appear, like resistance, politics, the oppressed, and conversation. With its humming buzz and murmur against the present situation, it is a collection of words refusing to remain silent.”— Lin Hsin I(Associate Professor at the Institute of Applied Art, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University) ▍People’s Theater Practitioners Asian People’s Theatre Festival Society (Hong Kong)/Assignment Theatre (Taiwan)/Centre for Applied Theatre, Taiwan (Taipei)/Grass Stage (Shanghai)/Langasan Theatre (Hualien)/Makhampom Theatre Group (Ching Dao Bangkok)/Oz Theatre Company (Taipei)/Philippine Educational Theater Association, PETA (Manila)/Shigang Mama Theater (Taichung Shigang)/Teater Kubur (Jakarta)/Teatro em Casa (Mozambique)/Theater Playground SHIIM (Busan)/Trans-Asia Sisters Theater (Taiwan)/WANG Mo-lin (Taiwan)/Wiji Thukul (Solo)/Yasen no Tsuki (Tokyo) ▍Recommenders Lai Shu-Ya /Director, Centre for Applied Theatre, Taiwan Chen Chieh-Jen/Artist Chen Hsin-Hsing /Professor, Graduate Institute for Social Transformation Studies, SHU Chou Hui-Ling/Professor, Department of English, NCU Hsu Jen-hao/Associate Professor, Department of Theater Arts, NSYSU Kuo Li-Hsin/Professor, Department of Radio & Television, NCCU Shih Wan-Shun/Associate Professor, Department of Taiwan Literature, NTHU Yao Lee-Chun/A Director of Body Phase Studio–Guling Street Avant-garde Theatre (GLT) ▍Characteristics of this book 1.Beyond the geographical limitations of Taiwan and East Asia, combined the context of Inter-Asian societies and Third-World society, appreciate the theater work methods that are intertwined with folk culture and community traditions, and promote the practice of public theater. 2. This book focuses on depicting network relationships in specific historical periods, and explores how the cooperation and interaction of troupes in these heterogeneous regions occurred. And how do these interactions affect the characteristics and forms of popular theater organizations in the transition of different policies? 3. What this book looks back on is not only the continuation and development of troupes but also the sudden change or gap between new people theaters and old people theaters.

作者介紹

作者介紹 Ratu Selvi Agnesia, Glecy Cruz ATIENZA, AU Sow Yee, BAEK Dae-hyun, Richard BARBER, Assane Alberto CASSIMO, CHUNG Chiao Dindon W.▍CURATOR OF THE OPENING NIGHTYAO Lee ChunTheater director, producer and festival director, film researcher and curator.The director of Body Phase Studio since 2007 and has been as Director of Guling Street Avant-garde Theatre (GLT) since 2008.▍PHOTOGRAPHERHSU Ping A documentary photographer. Over the past three decades, he has consistently documented the diverse phenomena of the post-Martial Law Taiwan and on off the stage of modern theaters.▍AUTHORS Ratu Selvi Agnesia/A young female theater researcher active in Jakarta. Glecy Cruz ATIENZA/A Professor at the College of Arts and Letters, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City.AU Sow Yee/A guest writer for the online magazine No Man’s Land; Co-founder of Kuala Lumpur’s Rumah Attap Library and Collective.BAEK Dae-hyun/A producer and an actor for the works of SHIIM.Richard BARBER/A theater worker and independent scholar working as the co-director of Free Theatre in Melbourne, Australia and advisor to the Makhampom Theatre Group in Thailand.Assane Alberto CASSIMO/A coordinator and founding member of Associação Teatro em Casa.CHUNG Chiao/A playwright, theater director, poet, and the artistic director of Assignment Theatre.Dindon W.S./The Director of Teater Kubur.Muhammad FEBRIANSYAH/A lecturer at School of Social Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang.HAN Jia-ling/A history and rural education scholar and activist. HONG Seung-yi/Currently working at Theater BAKK.Hsiao-Chuan HSIA/A Professor at the Graduate Institute for Social Transformation Studies, Shih Hsin University.KUO Liang-ting/An adjunct lecturer at the Chinese Department of National Chung Cheng University.LEE Show Shin/An artist from community people’s theater and a family care worker.LIU Hsin-hung/The main participant of Yuquan Training since 2015.Adaw Palaf LANGASAN/The founder and director of Langasan Theatre.WANG Chu-yu/A contemporary artist, performance artist, and curator based in Mainland China.WANG Mo-lin/A theater director, performance artist and cultural critic Robin WEICHERT (Tokyo).Robin WEICHERT/A teacher of Hosei University, Tokyo.WU Sih-Fong/A theater Critic, Associate editor of Performing Arts Forum (Macau).ZHAO Chuana/A writer, theater maker and curator who creates alternative and socially engaged theater in China. Also, he is the founding member and mastermind of the theater collective Grass Stage since 2005.Jonathan S. PARHUSIP/Ph.D. of the Institute of Social Research and Cultural Studies, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University.Kin TONG/A translator and researcher on psychoanalysis theory.Qi LI, Zikri Rahman, Joyce C.H. LIU主編▍EDITORS INTRODUCTIONQi Li Qi Li is a Ph.D. student in Institute of Social Research and Cultural Studies in National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University. She came to Taiwan out of curiosity, then got a journey full of adventures. Her ongoing projects focus on life stories of the small theater practitioners, the technologies of mobility and governance in contemporary conditions, and the political-economic transitions on both sides of the Taiwan Strait over the last half-century. She writes articles and reviews for independent media and research institutions based in different countries. She was the coordinator

試閱文字

導讀 : Introduction

Where Are the People?

How Could the People’s Bodies Voice Themselves in the Form of

Theatrical Aesthetics?

Joyce Chi-hui LIU

Translated by Kris CHI

Proofread by LO Timothy and Zikri RAHMAN

Whose Faces of People’s Theater Has This Book Shown?

The book held in your hands—Where are the people: People’s Theater in Inter-Asian Society—is the result of the “Workshop on People’s Theater in Inter-Asian Society” hosted by the International Institute for Cultural Studies of National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University in December 2018. We invited theatrical practitioners and researchers from Jakarta, Manila, Bangkok, Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Hong Kong, Tokyo, Busan, Maputo, Beijing, Shanghai, Hualien, Taichung, and Taipei to engage in this three-day activity.

Southeast and Northeast Asia experienced similar and interweaving historical processes. After World War II, Asian regions entered the Cold War phase. To follow the implementation of containment with the strategic foreign policy of the United States and the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the U.S. and Japan, various right-wing authoritarian governments supported by the U.S. declared martial law at different stages and mounted internal purges. Since the 1950s, cultural workers and intelligentsia in the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore had been arrested and accused of participating in communism; Taiwan, Japan, and Korea also had the same kind of anti-communist purges. In the 1980s, people’s theaters began to grow in the Southeast Asian and Northeast Asian countries, and the cross-region connection in the inter-Asian society was established, which was significantly meaningful in the context of this history.

“People’s theater” belongs to the people. It is the theater created by the people and speaking for the people; it has appeared in history in diverse forms. Romain Rolland’s Le Théâtre du peuple was published in the early twentieth century. In this1903 book, Rolland declared that the people’s theater should not be the theater defined by the State because the State belongs to the past, while the theater of the people belongs to the future. Theaters of the State and the palace offered conservative and petrified forms. From the French Revolution to the October Revolution in Russia, the people’s theaters were born to serve the people. The State withdrew from the theater and the people entered the scene, hence the names such as People’s Theater and Popular Theater which emerged from different socio-political situations in various sites.

The most influential and widespread form of the people’s theater is “Theatre of the Oppressed,” advocated by Augusto Boal during the 1950s and 1960s in Brazil. Inspired by the Pedagogy of the Oppressed, the work of his good friend, Paulo Freire, Boal conceived “Theatre of the Oppressed” as a site for the oppressed to think about their dilemma in life. The audiences in this theater are also participants. By confronting their problems, arguing with one another, challenging the law, and playing roles together, they experiment with alternative methods to break away from the oppressive ideology. As the critical pedagogy suggested by Paulo Freire, critical consciousness should come from the critical self-awareness of the people themselves. They need to say no to be the container in which the superiors can inculcate regulations, decline to obey unreasonable conditions, and discern the emergence of various oppressive ideologies in their societies. Through their participation, they reveal the reality by questioning and challenging various myths which have been taken for granted for so long.

The underclass voices through the theater, in which the people carry out various forms of radical democratization. Such a phenomenon appears both on the African and Asian continents. Around the 1960s and 1970s, “Theatre for Development” appeared in Africa, and folk theaters with different approaches and techniques also sprang in Asian regions. For example, during the martial law period in the Philippines, a group of artists and teachers formed the Philippines Educational Theater Association (PETA) in 1967, which was the predecessor of Theatre for Development; during the 1970s and 1980s, the student movement in Korea triggered “Madang Theater;” in the 1970s Sakurai Daizō started “Tent Theatre.” These different experimentations are all expressive forms of people’s theater. For nearly three decades, various forms of people’s theater have been developed in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia, India, and China.

In this book, we will see the theatrical practitioners in various places in the Inter-Asia society. From the Cold War to the post-Cold War era, they respond to the complex problems in various regions through their unique ways of confronting different political and social contexts. For example, in the case of Taiwan, both Wang Mo-lin and Chung Chiao are too influential to be ignored, inspiring various theater groups and theatrical works. The practice of theater emerged and bloomed in Southeast and Northeast Asia. I can only invite readers to read through the paths trodden by these theatrical practitioners. Herewith, I believe everyone will have a clear outline of the intricate map of the people’s theater in the Inter-Asia society.

What Kind of Problem Should We Ponder Over via People’s Theater?

I propose that we contemplate the following questions:

How can the body bring forth critical consciousness? How can people’s theater manifest its theatrical aesthetics? What is today’s notion of the people? Can theatrical aesthetics change society or the State? Can the theater disrupt the social relation or the relations of its production?

First, how can the body raise critical consciousness? How can people’s theater manifest its theatrical aesthetics?

Bodies in people’s theater should not only be the vehicles of external “aesthetic formalism” or “body language.” Instead, they are the bodies inscribed with the materiality of historical memories and bodily feelings and, to a certain extent, even expose the people’s subject positions. Historical memories and physical sentiments of this sort are overlaid with the oppressive systems composed of complicated institutions, legislations, class, and ideology. Behind such an unjust system is the epistemology that makes up the system.

Teater Kubur from Indonesia is the best example of this. For thirty years, Dindon W.S., the director of the troupe, has invited people living nearby the cemetery of East Jakarta to join this troupe, especially the students who are out of school and entry-level workers who are alcoholics or receive a meager salary. From the amateur performing group to an award-receiving troupe, Dindon leads the troupe with his steadfast principle—by utilizing the elements in people’s lives andtheir daily languages. Dindon makes local languages and everyday objects such as bamboo, buckets, chairs, and dustpans the symbolic form or metaphors of daily life to evoke bodily feelings to observe the situations. From the Indonesian New Order era to the present age of globalization and neoliberalism, people endure oppression in different forms, which Teater Kubur then criticizes.

In their opening performance during the 2018 workshop, the debate of the Indonesian congress members in discussing developmentalism was projected onto the background. On the stage, two office chairs were being aggressively pushed around. Office chairs are the metonymy of congress in moving the development acts. This scene highlights the incompetence of people who cannot resist neoliberalist development by manipulating the governmental apparatus. Like the bamboo, dustpans, or buckets, which Dindon frequently uses, these everyday life objects or their traditional culture are not merely decorative props in his works. Instead, it is a potent metaphor to trigger the body’s critical power. Besides carrying out the energy with critical consciousness to emancipate politics through bodies, people’s theater demonstrates theatrical aesthetics to us.

Similarly, another opening performance entitled Goodbye! mom, directed by Wang Mo-lin, also showed theatrical aesthetics’ immense strength. Hong Seung-yi and Baek Dae-hyun, actors from the Korean troupe Theater Playground SHIIM, presented the event of the 1970s Korean labor movement. In this incident, Jeon Tae-il immolated himself as an act of sacrificial protest against the government’s unjust treatment of the working class. In this play, the two actors played the role of mother and son. The mother recalled the moment before her son carried out the act of self-immolation. The slow bodily movement of the two actors highlighted the mother’s regret when she recalled the irreversible event and the tension between the decisive son and the cruel progress of historical time. The bodies and emotions onstage intensely triggered the bodies and feelings of the audience, situated in the slowly extended but irresolvable strain with great shock.

Second, what is today’s notion of the people? Can theatrical aesthetics change the society or the State? Can the theater disrupt the social relation or the relations of its production?

Plebeian, commoners, people, the populace, or proletarians refer to the people who offer their labor but have no autonomy in the relations of production. In the feudal period, proletarians could refer to the enslaved people or serfs consigned to unpaid servitude. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the term refersto the factory laborers whose time and labor were exploited. Nowadays, the oppressed proletarians are not only in the factories but also on-call workers driven by the gig economy or migrant workers in the corners of metropolises. These gig workers and migrants are restrained from organizing unions and gathering to protest for themselves. It is not easy for their voices to be heard.

最佳賣點

最佳賣點 : Where Are the People?

How Could the People’s Bodies Voice Themselves in the Form of

Theatrical Aesthetics?

At That Time, the Audience Really Stood Up.